August 11, 2025

Genome BC recently funded two Society Issues Competition (SOC) projects to investigate improvements for genetic testing for hereditary cancers. Intake 4 of SOC supports qualitative research to increase equitable access to and adoption of genomic technologies in healthcare.

The two projects explore different approaches to accessing genetic testing in the BC healthcare system: ‘cascade’ testing and population-based testing. While genetic tests can save thousands of lives, research is needed to gather rich information that reflects what communities in BC need, and data useful for evaluation and implementation within our healthcare system.

We speak to the following project leads about their upcoming work:

- Dr. Lesa Dawson, MD FRCSC from the University of British Columbia’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, on population-based testing for hereditary cancer prevention

- Dr. Intan Schrader, MBBS, PhD from the University of British Columbia’s Medical Genetics Department and BC Cancer, and Dr. Samantha Pollard from Simon Fraser University’s Faculty of Health Sciences and BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, on Parent-of-Origin-Aware genomic analysis to enhance cascade carrier testing

Tell us about the strategies you are researching that address the barriers to genetic testing for hereditary cancer risk.

Dr. Lesa Dawson: The focus of our project is population based testing (PBT), which means offering genetic tests to everyone without requiring their family history. Thousands of people in BC that are at high cancer risk — because they have inherited a faulty copy of genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 and RAD51C/D — are unaware of it because they don’t have access to genetic testing, which means they don’t have access to life-saving screening and prevention.

Dr. Samantha Pollard: Because family members share the mutation in high cancer-risk genes, a cancer patient’s relatives are encouraged to undergo ‘cascade’ testing. Unfortunately, very few family members undergo testing and are not benefitting from available, reimbursed prevention and management strategies.

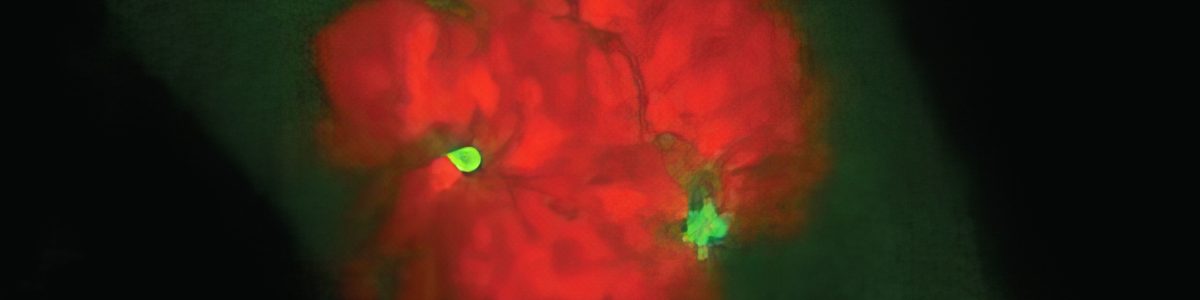

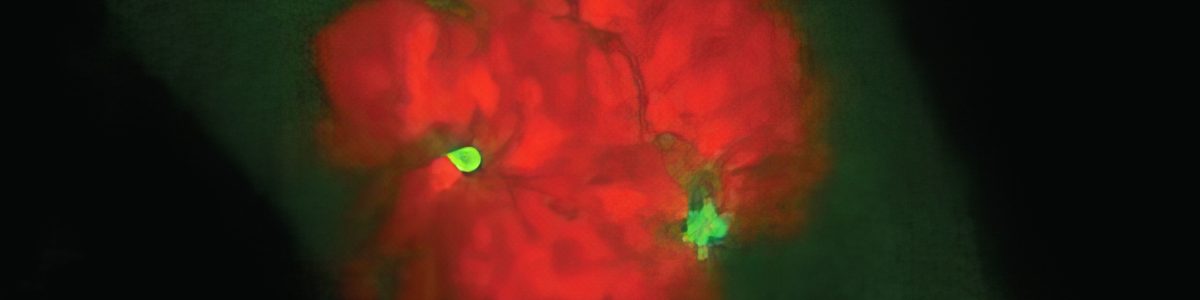

Dr. Intan Schrader: Our project looks at a novel, first-in-world technology called Parent-of-Origin-Aware Genomic Analysis (POAga) that was developed here in BC. Beyond what’s in the X and Y chromosomes, all genetic variation within a cancer patient’s inherited DNA sequence originates from one of their parents. We can tell which one with almost 99% certainty, using only a blood sample.

Dr. Pollard: POAga is a landmark advance in human genetics. It means that a second degree relative — like an aunt or uncle — on one side that may have been previously at a 25% risk could now be at 50% risk. With knowledge of elevated risk, family members may choose to initiate prevention and early detection interventions.

What are or some things that people don’t often know about genetic testing?

Dr. Dawson: A common misconception is the cost. At present, publicly funded testing is limited only to people who already have cancer or have a family history, because this system was designed back when tests were much more expensive. The cost of testing has now actually reduced to such a level that we need to rethink our strategy for who can access a test: the strategy that is dependent on family history is not always reliable and we should not restrict access based on this.

What are some current challenges in genetic testing?

Dr. Dawson: Access to genetic testing is a health equity issue. People of colour and marginalized communities face more barriers within the system to get testing. The current process requires many ‘hoops’ before a person can get a referral. In many cases, people might not have access to their family history or trust the system enough to pursue testing. We want to make cancer prevention equitable, accessible and safe for everyone.

Dr. Schrader: We know the uptake in genetic testing for extended relatives is very minimal. The numbers are even lower when you’re not of European ancestry. Minority populations are disproportionately impacted. POAga can be invaluable for people without access to their parents, people who are adopted, or those with fractured family histories.

What are some questions will you explore in this research?

Dr. Schrader: We want to understand what genetic risk clarification will mean to people. The efficient uptake of cascade genetic testing needs to align with the values and expectations of those who will be ultimately impacted.

Dr. Pollard: To date, POAga has only been available in research settings. To make it part of standard care testing at BC Cancer, we need data and evidence that decision makers can use. We need to address the barriers to implementation and adoption. We’ll be engaging with patients, families, healthcare providers, and decision makers from project outset, then combining this with clinical validation before implementing iteratively, with evaluation processes, within the Hereditary Cancer Program.

Dr. Dawson: We want our participants to tell us what they need in a genetic testing program so that we can design for a new model of care. For example: What specific genes do people want tested? At what age would they be most willing to be tested? Would they prefer a blood or saliva sample? Or how would they like to be told the results? Do they want them disclosed immediately, or at a predetermined time? We also need to ensure that our healthcare system is ready to provide more screening and prevention as the demand for access increases. When we have answers to these questions, we can validate, pilot, and prepare for large scale implementation.