January 12, 2026

Highlights

- KelpGen, a project funded by Genome BC, has filled information gaps for the conservation and management of kelp forests in British Columbia

- Researchers from the University of Victoria, the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre and the Kelp Rescue initiative have gathered genetic information on two keystone kelp species, bull kelp and giant kelp, in BC to understand their populations and vulnerabilities to climate change

- The Kelp Rescue Initiative is currently using the new information through field trials for kelp restoration

- Genetic information can contribute to guidance for restoration activities such as where to source or plant seeds, so BC kelp forests can be managed strategically, sustainably and effectively

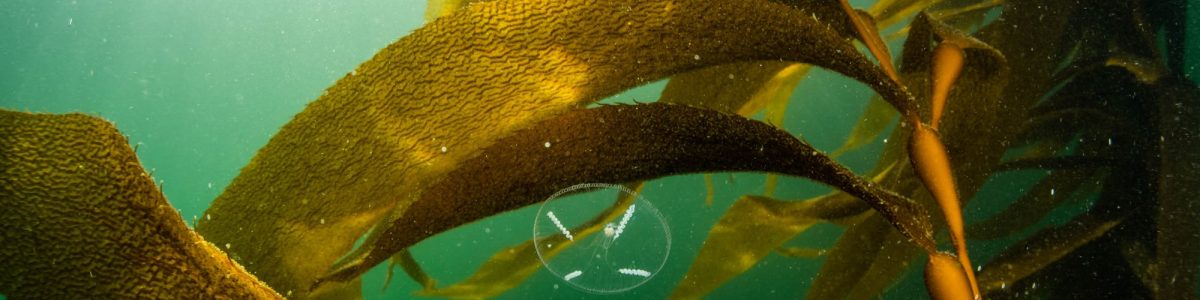

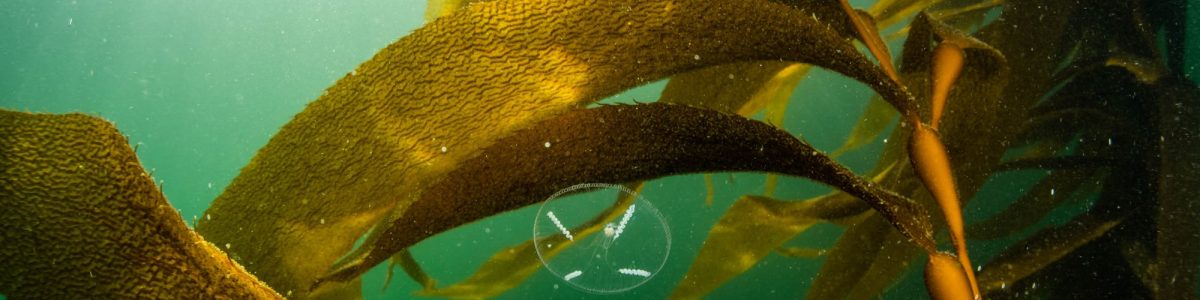

VANCOUVER – Beneath the coastal waters of British Columbia are vast, dense populations of algae integral to our ecosystems. For thousands of years, these kelp forests have nurtured fish, mammals and invertebrates, while providing natural climate solutions by removing nitrogen and storing carbon. Kelp forests also nurture species such as Pacific salmon and abalone that are vital to Indigenous food systems and BC’s fisheries industry.

Among other factors, climate change and increasingly long, intense periods of marine heatwaves have caused an accelerated decline in kelp forests worldwide. BC’s are no exception. For the province, this signals a risk to valuable biodiversity as well as kelp’s economic contributions through fisheries and carbon sequestration. In 2023, kelp forests worldwide were estimated to generate an average of US$500 billion annually.

Detailed information is needed to support the restoration, conservation and management of kelp forests in BC. This was the goal of KelpGen, a Genome BC funded project led by Dr. Gregory Owens and Dr. Jordan Bemmels from the University of Victoria, Dr. Sean Rogers, Executive Director of the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, and supported by Dr. Jasmin Schuster from the Kelp Rescue Initiative.

The team gathered genetic information on two keystone kelp forest species, bull kelp and giant kelp. These species were examined to determine population information and vulnerabilities to climate change. The evidence can be used to guide conservationists, policymakers and fishery and aquaculture practitioners towards efficient, sustainable management of our kelp forests.

“There are major knowledge gaps when it comes to kelp genetics,” said Dr. Schuster, whose role involved validating data through restoration field trials with the Kelp Rescue Initiative. “Restoration isn’t just about replacing what’s lost. We need to rebuild kelp forests that can thrive in tomorrow’s oceans.”

The results from KelpGen support a strategic approach to kelp restoration by identifying the genetic factors for adaptability and resilience to stressors, as well as each population’s genetic health.

“Some populations have the genetic composition to respond to future warming events, while others don’t,” said Dr. Owens. “Genetic information can tell us which populations to source restoration seeds from, and which areas need the most support, so we know where to focus conservation efforts.” Such efforts include outplanting, which involves transferring young kelp from the lab to the natural environment.

Dr. Bemmels noted that there are great differences in kelp genetic diversity levels and susceptibility to the results of inbreeding. “Again, it suggests we can come up with optimal strategies for sourcing and culturing kelp in the lab to ensure that outplanted populations have the ability to thrive.”

By mapping the genetic diversity of kelp forests around the province, the team found six genetic clusters in bull kelp and seven in giant kelp, all found in distinct geographic regions. Knowing where genetically similar groups exist can help point conservation efforts in the right direction.

For Dr. Owens, the data is vital to address a regulatory gap around limits to kelp transplantation. The team hopes that this can lead to the designation of formal zones for conservation or seed-transfer, as well as guidance around kelp transfer for aquaculture practitioners.

The project also notably resulted in the development of draft reference genomes for BC bull kelp and giant kelp. Prior to this, the only reference genomes available for these species were from the United States, which contain genetic differences.

“Local adaptation is specific to conditions such as current, light and temperature,” said Dr. Schuster. “Moving seed stock without considering these genetics can lead to poor survival rates. When completed, the local reference genomes can be used as foundations for future studies on kelp in BC.”

“This project highlights the uniqueness and value of BC’s biodiversity that we don’t often see, and how genomics can be used as a strategic tool for protection, recovery and sustainability,” said Dr. Federica Di Palma, Genome BC’s Chief Science Officer and Vice President, Research and Innovation.

“Before this project, we knew almost nothing about kelp genomics in BC,” said Dr. Owens. “Now, we can look at the genetic makeup of the populations here and ask, how are they going to do in 2050 or 2100, with the changing climate?”

– 30 –

Contact: Genie Tay, Communications Specialist